Cycling has long been hailed as the ultimate eco-friendly and health-conscious mode of transportation. https://discerningcyclist.com/author/admin/ Cycling has long been hailed as the ultimate eco-friendly and health-conscious mode of transportation. Yet, despite the growing emphasis on sustainability and urban mobility, bicycle production in the European Union has seen a significant drop. In 2023, EU member states produced 9.7 million bicycles—a sharp 24% decrease from the 12.7 million produced in 2022. What’s causing this surprising downturn, and does it signal the end of the cycling revolution? The Numbers Behind the Decline According to Eurostat’s latest data, bicycle production declined in 14 of the 17 EU countries that reported figures for 2023. Notably, some of the largest producers experienced the steepest declines: Romania : A drop of 1 million units, bringing total production down to 1.5 million. Italy : A reduction of 0.7 million bicycles, leaving production at 1.2 million. Portugal : A decrease of nearly 0.4 million, though it still led the EU with 1.8 million units produced. Poland : Produced 0.8 million bicycles, but it also saw a decline. This downward trend comes at a time when many European cities are actively promoting cycling as a means to reduce urban congestion and carbon emissions. So, why is production faltering? Possible Causes of the Decline The decline in bicycle production can be attributed to a variety of economic, social, and market-driven factors: Economic Uncertainty The lingering effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, rising inflation, and broader economic instability have led to reduced consumer spending. People may be prioritizing essential goods over discretionary purchases like bicycles. Supply Chain Disruptions Global supply chain issues, including shortages of raw materials and components like aluminum and electronic parts for e-bikes, have likely hampered production capabilities. Shift to E-Bikes While traditional bicycle production is declining, the demand for e-bikes continues to grow. E-bikes are typically more expensive and complex to manufacture, requiring specialized parts that may not be readily available, contributing to overall lower production numbers. Second-Hand Market Growth A thriving second-hand market for bicycles has emerged in recent years. Many people are opting to refurbish or buy used bikes rather than purchase new ones, reducing demand for new models. Environmental Regulations Stricter EU environmental regulations for manufacturing processes could be impacting the speed and cost-efficiency of production, especially in countries with older production facilities. Is the Cycling Revolution Over? The decline in production might seem like a step backward for the cycling movement, but it’s essential to view this trend in a broader context. Urban cycling continues to thrive in many European cities, with increased investments in infrastructure and growing popularity of bike-sharing services. The drop in production could represent a market adjustment rather than a collapse of the cycling revolution. Some experts argue that shifting consumer habits, such as a preference for shared mobility or e-bikes, reflect an evolution of the cycling culture rather than its demise. While traditional bicycle production may have decreased, innovations like e-bikes and cycling-friendly urban planning are helping the movement adapt to modern needs. What Could Reverse the Trend? For the EU to regain its footing as a leader in bicycle production, several strategies could help: Boosting E-Bike Production Manufacturers should pivot toward e-bike production to meet rising demand. Governments can support this by offering subsidies and incentives for e-bike purchases and production. Investment in Green Manufacturing Upgrading manufacturing facilities to meet environmental standards while improving efficiency could help lower production costs and increase output. Stimulating Local Demand National governments and local authorities could launch campaigns to encourage bike ownership, including tax breaks or subsidies for traditional bicycles. Supply Chain Resilience Diversifying supply chains and investing in local production of components could reduce reliance on imports and prevent future disruptions. SEE MORE CITY TRANSFORMATIONS A Hopeful Outlook for Urban Cyclists While the production decline is concerning, it is by no means the end of the cycling revolution. Urban cycling remains a cornerstone of sustainable transportation, and the challenges facing the industry present opportunities for innovation. Investments in e-bikes, better infrastructure, and green manufacturing could pave the way for a stronger, more resilient bicycle industry in the EU. The cycling movement is far from over. It’s evolving. With continued support from governments, industry leaders, and cycling advocates, the future of urban mobility remains bright. After all, as cities grow denser and the fight against climate change intensifies, bicycles will remain a vital part of the solution. London daily cycle journeys rocket 26% on 2019 Thursday, 12 December 2024 https://cyclingindustry.news/author/jonathon_harker/ Transport for London has shared some hugely encouraging statistics, noting that daily cycle journeys have increased 5% since 2023, and a notable longer term rise of 26% since 2019. Perhaps subverting expectations and gloomy headlines about the perils for cities during the work from home boom, London has seen an increase in commuters (and others) on the capital’s streets and opting for pedal power over pre-Covid times. The numbers form a strong brace of longer term statistics for cycling together with the finding that cycling traffic is up almost 10% in England over the past decade. While the industry grapples with significant current challenges, the broader trend appears clear – there are more cyclists in England, indicating that the market is expanding (or at the very least people are cycling more often, which almost equates to the same thing, arguably). Inevitably, there’s also an argument for the low cost of cycling vs other modes of transport during a cost of living crisis. 1.33 million cycle journeys in London per day The new TfL data shows that the number of daily cycle journeys increased in 2024 to an estimated 1.33 million journeys per day. The growth was strongest in central London, with an 11.6% increase between 2023 and 2024. Inner London saw a 4.2% increase and outer London saw a 3.8% increase. Working with London boroughs, TfL has increased the length of the strategic cycle network from 90km in 2016 to over 400km in September 2024, meaning that 27.4% of Londoners live within 400 metres of the cycle network. In 2023/24 alone, TfL launched 20 new Cycleways routes, connecting more than 600,000 Londoners to the network. TfL’s continued work with the boroughs in expanding the Cycleway network is working towards the Mayor’s target of 40% of Londoners living within 400m of a Cycleway by 2030. Cycleways across London that helped reach the 400km milestone include Cycleway 23 in Hackney, C9 in Hounslow, C25 in Waltham Forest and C6 in Camden, with each protected cycleway providing a safer route for people choosing to cycle. Delivering high-quality new Cycleways will support Londoners of all backgrounds and abilities to cycle safely, encouraging greater diversity in cycling, said TfL. It is continuing work to expand the network, with construction starting in January on C34 (Wood Lane to Shepherds Bush). The route will include protected cycle lanes, new pedestrian crossings and new bus lanes. Next year will see the completion of several major borough-led Cycleways, including Rotherhithe to Peckham, Enfield to Broxbourne and Deptford Church Street. London’s Walking and Cycling Commissioner, Will Norman, said: “It is tremendous that the number of Londoners cycling in the capital continues to grow year-on-year. We are extremely proud of our work to expand the protected cycleway network. This data shows that if you build the right infrastructure, people will use it. We will now look to build on this progress, working closely with boroughs to increase the cycle network even further. Enabling more people to make their journeys by walking, cycling and using public transport is key to building a safer and greener London for everyone.” Alex Williams, TfL’s Chief Customer and Strategy Officer, said: “Walking and cycling is key to making London a sustainable city, so it’s very encouraging to see this new data, which shows that there continues to be a significant number of journeys cycled or on foot. We have made great strides expanding the cycle network throughout London from 90km to over 400km and are continuously working to increase this number. We’re determined to ensure that the way people travel in London is not only healthy and sustainable but also affordable, which is why we are working closely with boroughs to transform our roads and invest in our transport network, enabling even more people to make their journeys by walking, cycling and using public transport.” Oli Ivens, London Director at Sustrans, said: “This new report showing more Londoners are choosing to cycle as part of their everyday journeys is great news from both a health and environmental perspective. Incorporating activity into daily life has huge benefits for businesses too thanks to better physical and mental health, so it’s encouraging to see more people cycling. At Sustrans we’re hugely proud of our work supporting TfL and London boroughs in the roll-out of new cycleways. We continue to design, build and activate new schemes and see huge opportunity for increased cycling in outer-London areas, and an acceleration of the integration of active travel with public transport.” Mariam Draaijer, Chief Executive of JoyRiders, said: “It’s great to see that overall cycling numbers in London are going up and that it is increasingly seen as a viable alternative form of transport. Cycling can often be faster and more reliable than other forms of transport. It’s important though to point out that there still needs to be more work done especially in London’s outer boroughs and we urgently need to work on closing the gender gap in cycling.” Tom Fyans, Chief Executive Officer at London Cycling Campaign, said: ”London really has embraced cycling. Thanks to sustained investment by TfL, cycling now makes up a third of all tube journeys – it’s a mainstream, mass mode of transport that is healthy, safe, and both climate and congestion busting. TfL’s latest report underlines the urgency of the next steps needed – delivering high-quality safe cycle routes throughout outer as well as inner London, into every borough. That’s what will help London become the clean, green, healthy city the Mayor has committed to.” As noted in some of the above quotes, there’s plenty of room for improvement on those current daily cycle journey statistics and the infrastructure that makes it all possible. Share and hire bikes will have played their part in the rise, and there are some difficulties there too – like those created by some dockless hire bike users – that appear on the cusp of being resolved.

1. Brompton Bicycle: The Icon of Urban Cycling Brompton isn’t just a brand; it’s a revolution on wheels. Born in a London flat in 1975, Brompton began with a clear mission: to transform urban commuting. And boy, did they deliver. Every Brompton bike folds down fast into a brilliantly compact package, making it the go-to choice for city dwellers navigating crowded train platforms and tiny apartments. Innovation at its Core What sets Brompton apart is their relentless pursuit of perfection. Their bikes aren't just made; they're engineered to ensure that every ride is smoother, every fold is quicker, and every bike lasts longer. The introduction of electric models has only broadened their appeal, proving that innovation is still at the heart of their design. A Community of Riders But Brompton's impact goes beyond the bikes themselves. The brand has cultivated a vibrant community of riders worldwide. From the bustling streets of Tokyo to the hills of San Francisco, you’ll find Brompton owners racing, touring, and commuting. Annual events like the Brompton World Championship not only showcase the bike’s prowess but also bring enthusiasts together in a celebration of folding bike culture. Sustainability and the City In a world where urban mobility is increasingly about eco-friendly choices, Brompton stands out by offering a sustainable, healthy way to navigate the city. Their commitment to local manufacturing not only supports the UK economy but also keeps their carbon footprint lower than many competitors. 2. Pashley Cycles: Embracing Tradition with Modern Flair As England's oldest bicycle manufacturer, Pashley Cycles holds a special place in the hearts of British cyclists. Founded in 1926, Pashley prides itself on producing hand-built bikes that blend timeless design with modern functionality. Classic Designs, Contemporary Needs Pashley's range includes everything from classic city bikes and cargo bikes to stylish cruisers, each crafted with attention to detail and a nod to heritage. But it’s not just about looks; these bikes are built to meet today’s cycling demands, combining comfort with utility. Supporting British Craftsmanship Each Pashley bicycle is a testament to British craftsmanship, made using traditional techniques and locally sourced materials wherever possible. This commitment to quality ensures that every Pashley bike isn’t just a means of transport; it’s a piece of art. 3. Condor Cycles: Crafting Performance and Precision Founded in 1948, Condor Cycles stands out for its commitment to producing tailor-made road and track bicycles right in the heart of London. Known for their bespoke service, every Condor bike is fitted and built based on individual rider needs, ensuring top performance whether on city streets or racing circuits. Customization at Its Best Condor's unique selling point is their customization process. Customers can select from various frames, components, and finishes to create a bicycle that not only fits perfectly but also reflects their personal style and riding preferences. A Legacy of Innovation Over the decades, Condor has maintained a pioneering spirit, constantly evolving their designs to incorporate new technologies while preserving the handcrafted quality that defines them. Their bikes have been ridden by champions in world-class competitions, proving that Condor’s dedication to quality translates into real-world success. 4. Whyte Bikes: Pioneering British Innovation Whyte Bikes, launched in the late 1990s, began with a clear focus: to improve the riding experience in British conditions. They pioneered geometry that enhances stability and handling on wet and wild UK trails, setting new standards in mountain bike design. Leading in Off-Road Technology Whyte is renowned for their innovative approach to mountain bike geometry, particularly their longer wheelbase and wider bar design that provide improved control and comfort. This design philosophy has helped them stand out as leaders in off-road biking technology. Committed to Trail Enthusiasts Whyte doesn’t just sell bikes; they foster a community of trail enthusiasts, regularly engaging in trail conservation efforts and promoting sustainable practices within the biking community. Their commitment extends beyond sales to ensure that riders have safe, enjoyable, and environmentally friendly places to ride. 5. Ribble Cycles: From Local Shop to Global Icon Ribble Cycles began its journey in 1897 in Preston, England, growing from a small local shop to a globally recognized brand. They are celebrated for delivering high-quality, cost-effective bicycles, catering to both professional athletes and recreational riders. Custom Built for Everyone Ribble stands out for their direct-to-customer model, which allows them to offer high customization at competitive prices. Using their online BikeBuilder and Advanced Bike Builder platforms, customers can specify everything from frame material to gearing and aesthetics. A Culture of Cycling Ribble actively promotes a cycling culture with a strong focus on accessibility and community engagement. They host events and rides, offer extensive customer support, and maintain an active presence in cycling communities online and offline. 25 British Bicycle Manufacturers Bickerton Portables (Kent): Specialists in portable and folding bikes for the urban commuter. Bird Cycleworks (Hampshire): Designers of rugged mountain bikes tailored for trail enthusiasts. Brompton (London): Iconic creators of the world-renowned folding bikes designed for city living. Boardman (London): Providers of high-performance road bikes for competitive and recreational cycling. Cotic (Peak District): Crafters of versatile gravel and mountain bikes built for adventure. Condor (London) Founded in 1948, stands out for its commitment to producing tailor-made road and track bicycles Dolan (Liverpool): Renowned manufacturer of track bikes with a pedigree in racing. Enigma Bikes (Sussex): Makers of bespoke gravel and road bikes, blending style with performance. Factor Bikes (Norfolk): Innovators of cutting-edge road bikes known for their engineering excellence. Field Cycles (Sheffield): Artisans of custom-built road bikes with a commitment to quality. Forme Bikes (Peak District): Developers of road bikes that balance performance with rider comfort. Genesis Bikes (Milton Keynes): Producers of gravel and road bikes, known for their reliability and innovative designs. Isen (London): Modern builders of stylish gravel and road bikes for the discerning cyclist. Mason (Brighton): Constructors of high-quality gravel and road bikes that emphasize durability and design. Moulton Bikes (Bradford-on-Avon): Pioneers of the unique folding bike, designed for optimal urban transport. Mycle (London): Innovators in the electric bike market, offering modern solutions for city commutes. Pashley Cycles (Stratford-upon-Avon): Historic manufacturers of classic city bikes with timeless appeal. Orange Bikes (Halifax): Manufacturers of premier mountain bikes, designed for extreme terrains. Orro Bikes (Ditchling): Creators of premium road bikes, focusing on performance and rider experience. Ribble Cycles (Bamber Bridge): Leaders in direct-to-customer road bikes, known for customization and value. Rourke (Stoke-on-Trent): Fabricators of custom-built road bikes with a focus on personalization and craftsmanship. Shand Cycles (Edinburgh): Builders of bespoke gravel bikes, designed for both performance and comfort. Starling Bikes (Bristol): Makers of handcrafted mountain bikes, praised for their innovative designs. Woodrup Cycles (Leeds): Traditionalists in road bike manufacturing, offering bespoke builds for discerning riders. Whyte (Hastings): Specialists in mountain bikes, designed to tackle the demanding British landscape. Velomont (Norfolk): New entrants crafting mountain bikes, focusing on durability and innovative features. British bicycle brands embody more than just manufacturing; they represent a lifestyle and a heritage that continues to inspire cyclists around the globe.

What a week last week! This entire issue is dedicated to the amazing women of African cycling. These women are quickly exhibiting their prowess on the bicycle and their fierceness as competitors. This year's Tour du Burundi hosted women from Benin, Uganda, Sierra Leone (the first professional international event), Senegal, Kenya, Burkina Faso, and Burundi. The dedication and hard work of our athletes, coaches, and staff, along with a strong focus on women's cycling on the continent, paid off in a big way at the Tour du Burundi. Everything we do at Africa Rising Cycling is aimed at preparing the current generation and training the next generation—local coaches, mechanics, and soigneurs —to excel in the sport we all love. The women of Team Benin started better than their performance in 2023; however, they were not up to where the coach, Salami Avoceiten, felt they could be. If you remember, Salami spent 6 weeks in the US in intensive coaching training, on and off the bike. He dedicated himself to the firehose of knowledge our coaches pointed his way and showed his maturity and understanding of the sport in Burundi. The full results are HERE. However, the first three stages only tell part of the story. The Benin women were doing better. However, they were not firing on all cylinders as a team. Salami took the time to reach out to Coach Adrien and Coach Jock, and Coach Jock spoke to the women with Salami and laid out a strategy for Stages 4 and 5. The women delivered -- BIG TIME! On Stage 4, Hermionne, Benin's veteran female, took 2nd place in the final sprint and moved into 3rd in the General Classification (GC) thanks to the incredible teamwork of the women on her team. Stage 5, she WON the stage and retained her 3rd place GC. This win was the first time a Benin cyclist (man or woman) won a stage in an international race. The team followed up their 2023 performance with a 3rd place Team Classification win. The final event was the Grand Prix of Burundi, which, as predicted, finished with a 14-woman sprint. Hermionne took 2nd, and 17-year-old Georgette, who recently participated in and completed the Junior Women's Road Race at the World Champs in Switzerland in September, finished 3rd! Another highlight was the first-time participation by the women of Sierra Leone. Africa Rising Cycling supported the Sierra Leonean women with a preparatory training camp and flights to the event. Despite the initial challenges of their first international race, the Sierra Leonean women fought daily to finish within the time limit. In the end, a young woman, Elizabeth, became the first Sierra Leonean woman to finish the Tour du Burundi. All these women showed incredible resilience and determination, quickly learning where they needed to be to race competitively with their peers. As our motto is 'always be training,' Sierra Leone coach Roxanne was there with the former National Champion of Sierra Leone, Isata, who had her debut as the National Coach of the Sierra Leone Women's Team. Isata was not only an asset to her team but also helped the Ugandan women. Finally, a big shout out to the winners from Burkina Faso and their coach, Veronique. African women's cycling is on a meteoric trajectory, with talented riders and equally talented women coaches paving the way!.

We are now winding the clock back to the mid to late 1960s. At the time Condor Cycles were sponsoring and supplying bikes to what was to become the Condor Mackeson Team. The shop number 90 Grays Inn Rd was always busy not with customers but with riders relating as to how they had, or not, won at the weekend. One rider in particular, being Italian, would only ride a Colnago and his name was Leo Cura . He had a cafe off Pall Mall and would participate in local road races. He wasn't interested in where he finished, he just enjoyed the spectacle. In the off season we would meet up at his house in Acton and do a 2.5 hour ride. Another Italian, always very tanned, would join us. This was George Beretta who lived in Neasden and before he drove a black cab for a Living he had a small specialist importer of cycle components importer called Beretta & Penny He always wore a World Championship racing cap with the bands with 'Il campionissimo' written on it. On one of our rides he said he owned a convertible American car, a 1960 Buick Invicta that he would like to sell and I would be interested as I had just passed my driving test. I could have it for £600. He gave me a couple of photographs and from this I could see the vehicle was huge! The car was white at the time and due to its inactivity mildew was more evident than paint. I have only recently disposed of those photos as I knew that George had died and that the car must have been sold many years prior to his death. However, walking amongst the stands at the 2024 Classic Car Motor Show at the NEC with Grant, where 380 clubs were exhibiting and stretching across 6 halls I came across a 1960 Buick Invicta. I immediately said that I am sure this is George's old car even though it is in Peppermint Green and no longer white. A quick look at the number plate and I was now even more positive. Subsequently a chat with the owner confirmed that it was the very same car which he had purchased from the family in 2017. The owner is Colin Shepherd and he spent 5 years restoring it before returning it to the road in 2022. In fact all the owner's hard work has paid off as it won 'Classic American Car Magazine Car of the Year 2024. It was such a coincidence to become reacquainted with the same car I had been offered all those years ago.

Cycling UK has shared findings from a new survey, which saw 70% of respondents indicating that they wanted to see more cycle-friendly routes across the country. The survey of over 4,000 people “found that there is wide public support for cycling and better infrastructure in the UK. However, despite this support, data revealed that while the majority of the UK (92%) can ride a bike, surprisingly less than half do.” Women and cycling Looking at the survey data surrounding cycling and gender, it showed that women were almost twice as likely as men to not know how to ride a bike (11% compared to 6%), with lack of confidence also being twice that of male respondents (41% compared to 19%). A separate report published at the start of the year, titled ‘What Stops Women Cycling in London?’[1] revealed that 77% of women who cycle experienced harassment and intimidation at least once a month. Cycling UK strongly believes we need to do more to encourage women to cycle by making it safer. The charity has proposed building a greater number of well-lit, protected cycle lanes to make active travel safe, accessible and easy. It has also highlighted groups and individuals that encourage a more inclusive cycling culture in the UK, through its 100 Women in Cycling annual list. 2023 Community champions like Eilidh Murray have made incredible progress campaigning tirelessly for women’s cycle safety in her position as a trustee for the London Cycling Campaign and as the coordinator of its new Women’s Network. Road safety while cycling The survey, commissioned by Cycling UK, went on to outline how men and women equally identified road safety as the main reason they don’t cycle, (50% and 47%, respectively). The data paints a picture that despite public support for cycling, the population ultimately remain hesitant because of concerns around road safety (48%). This is further mirrored by 70% of respondents wishing to see more cycle-friendly routes, that separate them from roads where they are more likely to be injured or killed. Cycling UK highlights that countless surveys and reports have been produced over the past years, which unanimously emphasise the seismic positive impact cycling can have. In February 2024, the IPPR found that if we properly invested in active travel, we’d save the NHS £17 billion over 20 years. But going back to 2018, a survey by Cycleplan identified three-quarters of respondents noticed an improvement in their mental health after cycling. The mental and physical benefits of cycling Digging deeper into the reasons why so many of the UK support more cycle routes and better infrastructure, the public collectively recognise the benefits it has to mental and physical health. When asked, ‘Which do you think are the three most important benefits of cycling’, respondents to Cycling UK’s survey most often selected: Improves physical health (60%) Boosts fitness (50%) Enhances mental health (38%) The majority of those aged 45 and over were the most likely to recognise the benefits cycling has to physical health and fitness, with an average of 62% compared to 46% of under-45s. People in this demographic were, however, less likely to see the important impact cycling has on mental health, with an average of 36% of over-45s citing mental health as an important benefit, while the average was 41% for under-45s. Both age groups equally wanted to see more people cycling, and age did not affect respondents’ support for more cycle-friendly routes and the promotion of cycling. Sarah Mitchell, Cycling UK’s chief executive, said: “In the latter stages of the previous government, we saw the conversation around cycling become increasingly divided. “Too many politicians and commentators were attempting to co-opt cycling as part of the culture wars, by driving a wedge between people who drive and people who cycle. “With the new Culture Secretary announcing an end to the era of culture wars, we are hopeful that this kind of divisive rhetoric will be put to bed once and for all. We encourage and support debate, but we need to actively encourage this to be evidence-led and with civility at its heart. “There is a clear desire from the UK to build better cycle infrastructure and get more wheels on the road. People overwhelmingly want to get around their communities without waiting in traffic for who knows how long or having to pay to put petrol in the tank, when it would be cheaper and quicker to go by bike or foot. “Cycle lanes are cheap to build, reduce emissions, improve public health and lead to less congestion. The public recognises the benefits of cycling and is desperate to enjoy them. With political backing and funding, we can make that future a reality.” Transport infrastructure and active travel investment Earlier this year, independent research from the Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR) called for at least 10% of total transport investment to go towards active travel. This wasn’t because people living across the UK widely support cycling, which they do, but because it benefits the economy, public health and the environment in a big way. Recognising what people want from the new government, Cycling UK is repeating calls for Labour to commit to spending 10% of the total transport budget on active travel to enable people to live happier, healthier and greener lives through cycling. Cycling UK wants to see cycling and walking prioritised by this government so we can create better joined-up transport for all communities across the UK. The charity maintains that local authorities need the security of this long-term funding to have the confidence to develop and deliver ambitious plans for active travel networks. The new Transport Secretary Louise Haigh has promised to deliver the biggest overhaul to transport in a generation, having recognised how investment in transport can help achieve Labour’s commitment to “growth, net zero, opportunity, and the safety of women and girls”. Cycling in particular has the potential to positively impact not just the transport sector but also Labour’s key missions to build an NHS fit for the future, boost economic growth, and so much more. Image credit: Cycling UK

The Grand Départ Classic is your chance to follow in the tyre tracks of the Tour de France pros . This three-day event (one-day riding) offers a unique opportunity to cycle on the same roads the pros will tackle in Lille, just one week later. Currently, every year, 12,000 men still die from prostate cancer. But by funding research into safer and more accurate diagnostic tests, you can help pave the way to a screening programme, where every man at risk will get an invite to regular tests that can spot cancer early enough for a cure. Register your interest to hear more Experience a once-in-a-lifetime cycling adventure Imagine setting off from the European Metropolis Lille, pedalling past breathtaking landscapes, through the idyllic rural towns of Lens and Bethune, and out into historic Flanders. You’ll feel the wind rush past you on the final wide, perfectly flat kilometre towards the city centre. Feel like a champion as you cross that finish line, knowing you’re helping save lives. The Grand Départ Classic offers a truly unforgettable experience. When: Friday 27 - Sunday 29 June 2025 Where: Lille, France 🚲 Route: Experience the thrill of cycling Stage 1 of the Tour de France 2025. Take on the 185km Lille loop, known for its scenic route and flat terrain. Find out more information about the route on Tour de France’s official webpage , where you can check out the 2025 route map and route profile. Sign Up Today More than a team When you sign up for the Grand Départ Classic, you become part of the Prostate Cancer UK cycling community, forging friendships that could last a lifetime. Here’s what you’ll get from us: A welcome pack stuffed with fundraising tips and information Expert training advice from professional coaches, including personalised plans. Dedicated help from our team every step of the way - contact us by email or phone whenever you have a question. The ride of a lifetime awaits The Grand Départ Classic is more than just a bike ride; it's a challenge, an adventure, and a chance to fund research into transforming diagnosis and developing the treatments men need – ensuring more men are diagnosed early enough to be cured. Register your interest today

The club’s speaker for September was Jez Cox, a former competitor in cycling and duathlon, who is now a commentator and presenter. He is freelance and has worked for all the leading sports channels including GCN, Eurosport and ASO. Jez’s cycling career started at the age of thirteen with the Twickenham CC where he came under the wing of Graham Macnamee and the Pedal Club’s former president Doug Collins. Starting in cyclo cross he moved on to road racing and by 1998 he was racing in France with the C.O. Chamalieres, an elite team, where he achieved good results. By 2003 he had returned to Britain to compete in duathlons (bike and run), a discipline which suited him very well since he had many victories over the next decade, including being ranked as the top British duathlete in 2007. But no one can be a professional athlete until reaching pension age and by good fortune Jez found a new metier at the Rebourne (Hertfordshire) fete where, in the absence of any other speaker, he was handed the microphone and discovered that he was a natural as a presenter; his commentating career developed from this moment. Alongside his journalism, in 2015 he set up a cycling academy in St Albans (Oaklands Wolves Cycling Academy). When he suggested this project to British Cycling he was told it was doomed to failure and this made him determined to prove them wrong. Perhaps BC didn’t know that he already had his foot in the door at Oaklands College, having done some consultancy work for them, but it is impressive that the academy is now flourishing nine years after its foundation. Unlike many other speakers (with the exception of John Dutton!) Jez was relatively optimistic about the current state of British Cycling. He feels that the departure of Team Sky has benefited the organisation, that the strong growth of women’s racing is an important advance and he believes it will be possible to bring at least some of the middle aged ‘mamils’ into cycling proper. Another hope is that facilities already existing in schools could be better used by the cycling world. Perhaps the most encouraging point for the Pedal Club is that this career started from an ‘old fashioned’ local club (the Twickenham CC, founded 1893 has produced many stars in the past). The great majority of Pedal Club members started in this way, and I’m sure we were all pleased to hear that this path can still lead to success in the twenty-first century. The Lunch was again held at the Civil Service Club in Whitehall and was attended by 34 members and guests. Chris Lovibond, September 2024. .

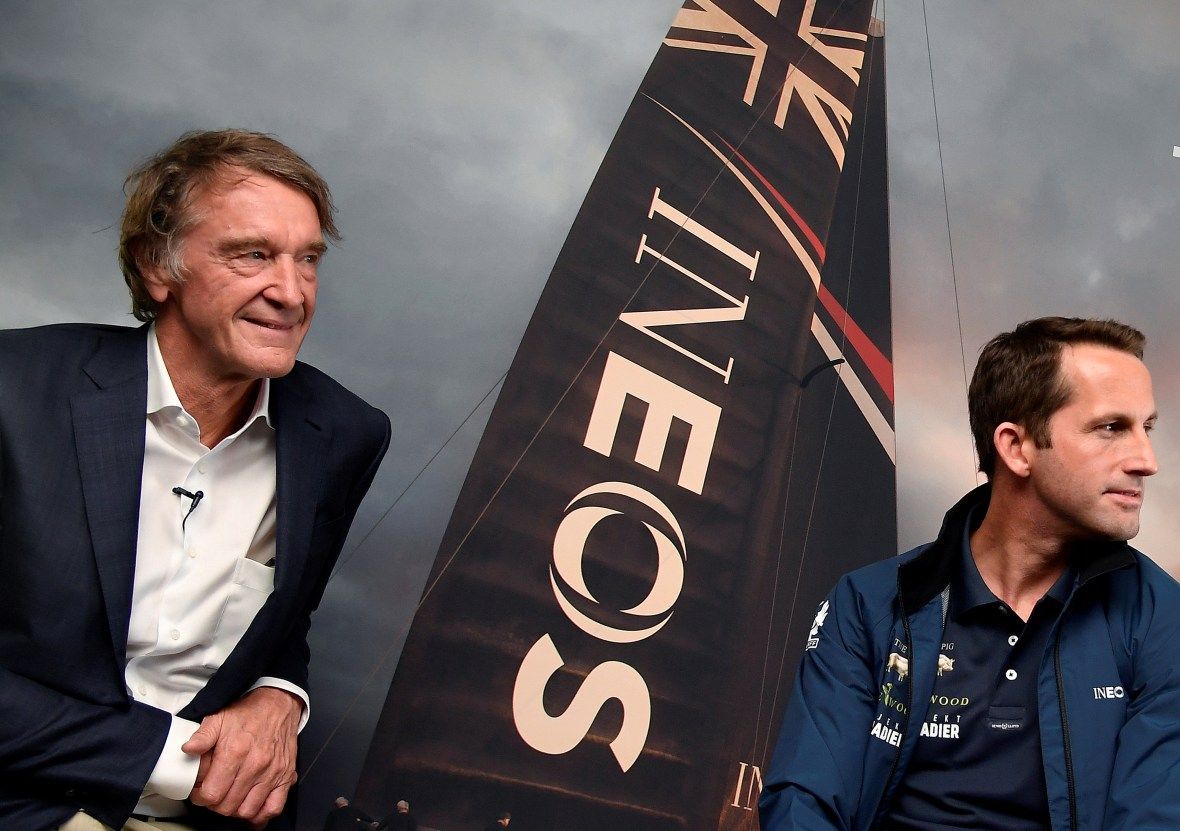

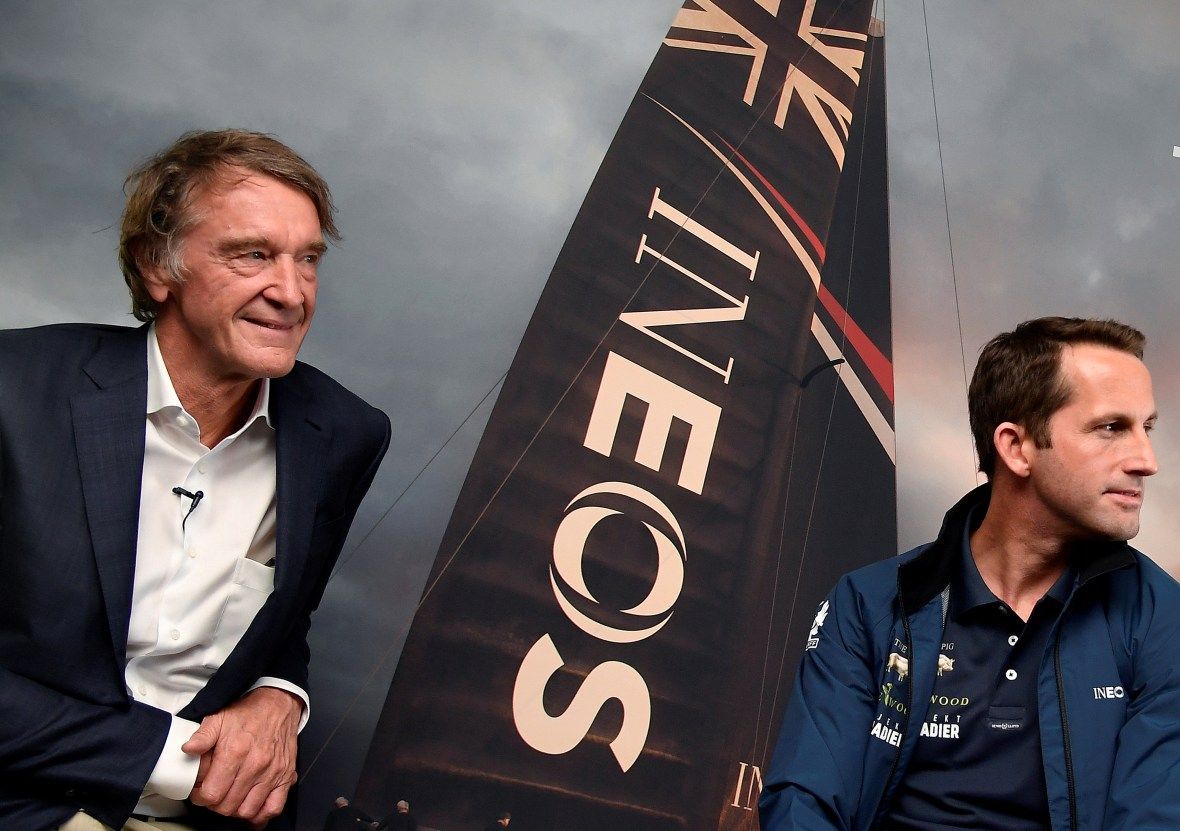

Take a stroll through Sir Jim Ratcliffe’s garden party. Here, on one side, the engineers of the Mercedes Formula 1 team that he co-owns are deep in conversation; over there three big All Blacks sweep the outdoor shed, the Ineos logo gleaming on their training tops. By the crystal-clear pond with its multi-coloured fish, Sir Ben Ainslie’s fingers dance on the buttons of a remote control, prompting a miniature boat to surf the artificially generated waves. In the middle of the garden, under the Renson Camargue Canopy, Sir Dave Brailsford bonds with the latest recruits to the backroom team at Manchester United. Ah, that’s Jean-Claude Blanc, chief executive of Ineos Sport, alongside him Omar Berrada, United’s chief executive, and the two across from them, Dan Ashworth, the club’s new sporting director, and Jason Wilcox, the technical director. Brailsford will speak about the future and may even pull out his iPhone and ask if he can take a photo of the group. It’s something he’s used before. In five years, he will say, you will want to look at this photo and reflect that these were the best men I ever worked with and we couldn’t have done any more. He’s good at this stuff, Brailsford; clever, charming, inspiring while seeming everyone’s best friend. Moseying from group to group in Sir Jim’s garden, the perceptive guest might notice who’s not invited. The cycling team. Ratcliffe took over Team Sky in May, 2019, turning it into Team Ineos. They launched at a gastro pub, the Fountaine Inn, in Linton, a quiet village deep in the Yorkshire Dales. Dropping from the sky, Sir Jim’s helicopter caused a stir. Beaming, Brailsford said it was a momentous day for cycling. Even Sir Jim himself was excited. “It’s the finest cycling team in the world, the finest riders in the world,” he said. At the time, this was true. Team Sky had won the Tour de France six times in the previous seven years. Only one other team had done this. Later that summer Egan Bernal won the 2019 Tour in the black and red of Ineos. It stands as the greatest victory achieved by any sporting entity backed by the petrochemical giant. For Brailsford, Bernal’s victory was a big moment. By winning seven out of eight, the team he founded had become the most successful in the history of the Tour de France. How come they are not at the garden party? Roll the calendar on five years, to March 2024 and in a plush Ineos office in Monaco, Ratcliffe speaks with the 2018 Tour champion Geraint Thomas for an episode of the bike rider’s podcast Watts Occurring. It wasn’t difficult to set up, as they both have homes in the principality and they’ve known each other since 2019. Back then they went on a bike ride together, east along the Mediterranean coast, had a coffee in Italy before returning home. So, for the hour-long podcast, they shoot the breeze like two mates. They talk about why Ratcliffe got into the ownership of sporting enterprises, his love of the bike, the day he crashed while riding with the four-times Tour de France winner Chris Froome but most of all they speak about Manchester United and football. If there was one player from United’s Treble-winning 1999 team he would like to have in today’s side, that would be Paul Scholes. And as they go gently, there is no mention of Ineos Grenadiers, the cycling team that Thomas still rides for and Ratcliffe still owns. Almost as if this team has become the mad aunt locked in the attic bedroom and never ever spoken about. One can only presume this reticence is because the performance has been underwhelming. And I mean on the desperate end of underwhelming. Since Bernal’s victory in 2019, the team has gone steadily downhill. Slow down boys or we’ll end up in Australia. From winning seven out of eight to not competing for the Yellow Jersey in the next five is some slide. So far this year, Ineos’s 30 riders have won a total of 14 races. Tadej Pogacar, leader of the UAE Emirates team, has 21 victories this season, his team has 72. Ineos have fallen so far that the best riders don’t want to go there. Speaking with his team-mate Luke Rowe on a more recent podcast, Thomas discussed the team’s travails. “I don’t think there’s one thing. There’s loads of things but they all add up,” he said. “I don’t think there’s one silver bullet that is the reason why we’ve struggled a bit but there’s numerous things. I think for now the main goal should just be, as a team, to be the best and the strongest and the most unified. We’re in it together, we’re all moving in the same direction and we’ve got these big goals and aspirations. Just get back to winning some bike races… it definitely needs a few honest conversations and looking in the mirror.” Ainslie, right, has reached the America’s Cup last four with the backing of Ineos and Ratcliffe Ainslie, right, has reached the America’s Cup last four with the backing of Ineos and Ratcliffe REUTERS/TOBY MELVILLE Brailsford created a highly successful team that relied to a dangerous extent on his presence. He left the team in December 2021 to head up Ineos’s sporting empire and even if the fall had begun before then, it accelerated after he left. When his efforts to lure Pogacar away from Team UAE failed, Brailsford knew it wasn’t going to get better. The chance to work on the rebuilding of United was one he wasn’t going to pass up. The restructuring of United is likely to lead to improvement. It’s impossible to imagine a club with its resources not getting better. There is, though, a caveat. So far, Ineos’s record in sport is at best mediocre. Apart from Bernal’s victory in the 2019 Tour, results have been deeply disappointing. Mercedes no longer dominate F1, Ineos Grenadiers are now a middle-of-the-road cycling team and the All Blacks have rarely seemed so beatable. Before Ineos announced its “performance partnership” with New Zealand rugby in late 2021, the All Blacks had played 612 Test matches with a 77.12 win percentage. With Ineos’s logo on their shorts in 32 Tests, the win rate slipped to 65.62. The company’s fortunes could change in Barcelona next month when the America’s Cup is decided. As things stand, Ainslie’s Ineos Britannia boat has reached the last four. I can easily imagine Ainslie skippering the first British boat to win the America’s Cup and will be surprised if Toto Wolff doesn’t get Mercedes back to the top of F1. And the All Blacks are not going to go on losing to Ireland and Argentina. It’s inconceivable that Manchester United will ever again finish as low as eighth in the Premier League and easy to envisage their return to the Champions League. That leaves Ineos Grenadiers, the cycling team and now the runt of the litter. I am not sure anyone at Ineos Sport cares that much.

The greatest gathering of Penny Farthing riders in London since the 1880’s! This extraordinary event will feature multiple solo and group Guinness World Records attempts, social & city rides, Victorian themed dinner & BBQ, with track racing at Herne Hill and London Olympic Velodromes. The organisers of this unique Penny Farthing Extravaganza, sponsored by Penny Farthing Homes, welcomes riders of all abilities from around the world. Register now and secure your place in the history books! Don’t miss your chance to make history in this thrilling weekend filled with Penny Farthing fun. Weekend Schedule including camping and evening events click here https://pennyfarthingworldrecords.com

Cycling has long been hailed as the ultimate eco-friendly and health-conscious mode of transportation. https://discerningcyclist.com/author/admin/ Cycling has long been hailed as the ultimate eco-friendly and health-conscious mode of transportation. Yet, despite the growing emphasis on sustainability and urban mobility, bicycle production in the European Union has seen a significant drop. In 2023, EU member states produced 9.7 million bicycles—a sharp 24% decrease from the 12.7 million produced in 2022. What’s causing this surprising downturn, and does it signal the end of the cycling revolution? The Numbers Behind the Decline According to Eurostat’s latest data, bicycle production declined in 14 of the 17 EU countries that reported figures for 2023. Notably, some of the largest producers experienced the steepest declines: Romania : A drop of 1 million units, bringing total production down to 1.5 million. Italy : A reduction of 0.7 million bicycles, leaving production at 1.2 million. Portugal : A decrease of nearly 0.4 million, though it still led the EU with 1.8 million units produced. Poland : Produced 0.8 million bicycles, but it also saw a decline. This downward trend comes at a time when many European cities are actively promoting cycling as a means to reduce urban congestion and carbon emissions. So, why is production faltering? Possible Causes of the Decline The decline in bicycle production can be attributed to a variety of economic, social, and market-driven factors: Economic Uncertainty The lingering effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, rising inflation, and broader economic instability have led to reduced consumer spending. People may be prioritizing essential goods over discretionary purchases like bicycles. Supply Chain Disruptions Global supply chain issues, including shortages of raw materials and components like aluminum and electronic parts for e-bikes, have likely hampered production capabilities. Shift to E-Bikes While traditional bicycle production is declining, the demand for e-bikes continues to grow. E-bikes are typically more expensive and complex to manufacture, requiring specialized parts that may not be readily available, contributing to overall lower production numbers. Second-Hand Market Growth A thriving second-hand market for bicycles has emerged in recent years. Many people are opting to refurbish or buy used bikes rather than purchase new ones, reducing demand for new models. Environmental Regulations Stricter EU environmental regulations for manufacturing processes could be impacting the speed and cost-efficiency of production, especially in countries with older production facilities. Is the Cycling Revolution Over? The decline in production might seem like a step backward for the cycling movement, but it’s essential to view this trend in a broader context. Urban cycling continues to thrive in many European cities, with increased investments in infrastructure and growing popularity of bike-sharing services. The drop in production could represent a market adjustment rather than a collapse of the cycling revolution. Some experts argue that shifting consumer habits, such as a preference for shared mobility or e-bikes, reflect an evolution of the cycling culture rather than its demise. While traditional bicycle production may have decreased, innovations like e-bikes and cycling-friendly urban planning are helping the movement adapt to modern needs. What Could Reverse the Trend? For the EU to regain its footing as a leader in bicycle production, several strategies could help: Boosting E-Bike Production Manufacturers should pivot toward e-bike production to meet rising demand. Governments can support this by offering subsidies and incentives for e-bike purchases and production. Investment in Green Manufacturing Upgrading manufacturing facilities to meet environmental standards while improving efficiency could help lower production costs and increase output. Stimulating Local Demand National governments and local authorities could launch campaigns to encourage bike ownership, including tax breaks or subsidies for traditional bicycles. Supply Chain Resilience Diversifying supply chains and investing in local production of components could reduce reliance on imports and prevent future disruptions. SEE MORE CITY TRANSFORMATIONS A Hopeful Outlook for Urban Cyclists While the production decline is concerning, it is by no means the end of the cycling revolution. Urban cycling remains a cornerstone of sustainable transportation, and the challenges facing the industry present opportunities for innovation. Investments in e-bikes, better infrastructure, and green manufacturing could pave the way for a stronger, more resilient bicycle industry in the EU. The cycling movement is far from over. It’s evolving. With continued support from governments, industry leaders, and cycling advocates, the future of urban mobility remains bright. After all, as cities grow denser and the fight against climate change intensifies, bicycles will remain a vital part of the solution. London daily cycle journeys rocket 26% on 2019 Thursday, 12 December 2024 https://cyclingindustry.news/author/jonathon_harker/ Transport for London has shared some hugely encouraging statistics, noting that daily cycle journeys have increased 5% since 2023, and a notable longer term rise of 26% since 2019. Perhaps subverting expectations and gloomy headlines about the perils for cities during the work from home boom, London has seen an increase in commuters (and others) on the capital’s streets and opting for pedal power over pre-Covid times. The numbers form a strong brace of longer term statistics for cycling together with the finding that cycling traffic is up almost 10% in England over the past decade. While the industry grapples with significant current challenges, the broader trend appears clear – there are more cyclists in England, indicating that the market is expanding (or at the very least people are cycling more often, which almost equates to the same thing, arguably). Inevitably, there’s also an argument for the low cost of cycling vs other modes of transport during a cost of living crisis. 1.33 million cycle journeys in London per day The new TfL data shows that the number of daily cycle journeys increased in 2024 to an estimated 1.33 million journeys per day. The growth was strongest in central London, with an 11.6% increase between 2023 and 2024. Inner London saw a 4.2% increase and outer London saw a 3.8% increase. Working with London boroughs, TfL has increased the length of the strategic cycle network from 90km in 2016 to over 400km in September 2024, meaning that 27.4% of Londoners live within 400 metres of the cycle network. In 2023/24 alone, TfL launched 20 new Cycleways routes, connecting more than 600,000 Londoners to the network. TfL’s continued work with the boroughs in expanding the Cycleway network is working towards the Mayor’s target of 40% of Londoners living within 400m of a Cycleway by 2030. Cycleways across London that helped reach the 400km milestone include Cycleway 23 in Hackney, C9 in Hounslow, C25 in Waltham Forest and C6 in Camden, with each protected cycleway providing a safer route for people choosing to cycle. Delivering high-quality new Cycleways will support Londoners of all backgrounds and abilities to cycle safely, encouraging greater diversity in cycling, said TfL. It is continuing work to expand the network, with construction starting in January on C34 (Wood Lane to Shepherds Bush). The route will include protected cycle lanes, new pedestrian crossings and new bus lanes. Next year will see the completion of several major borough-led Cycleways, including Rotherhithe to Peckham, Enfield to Broxbourne and Deptford Church Street. London’s Walking and Cycling Commissioner, Will Norman, said: “It is tremendous that the number of Londoners cycling in the capital continues to grow year-on-year. We are extremely proud of our work to expand the protected cycleway network. This data shows that if you build the right infrastructure, people will use it. We will now look to build on this progress, working closely with boroughs to increase the cycle network even further. Enabling more people to make their journeys by walking, cycling and using public transport is key to building a safer and greener London for everyone.” Alex Williams, TfL’s Chief Customer and Strategy Officer, said: “Walking and cycling is key to making London a sustainable city, so it’s very encouraging to see this new data, which shows that there continues to be a significant number of journeys cycled or on foot. We have made great strides expanding the cycle network throughout London from 90km to over 400km and are continuously working to increase this number. We’re determined to ensure that the way people travel in London is not only healthy and sustainable but also affordable, which is why we are working closely with boroughs to transform our roads and invest in our transport network, enabling even more people to make their journeys by walking, cycling and using public transport.” Oli Ivens, London Director at Sustrans, said: “This new report showing more Londoners are choosing to cycle as part of their everyday journeys is great news from both a health and environmental perspective. Incorporating activity into daily life has huge benefits for businesses too thanks to better physical and mental health, so it’s encouraging to see more people cycling. At Sustrans we’re hugely proud of our work supporting TfL and London boroughs in the roll-out of new cycleways. We continue to design, build and activate new schemes and see huge opportunity for increased cycling in outer-London areas, and an acceleration of the integration of active travel with public transport.” Mariam Draaijer, Chief Executive of JoyRiders, said: “It’s great to see that overall cycling numbers in London are going up and that it is increasingly seen as a viable alternative form of transport. Cycling can often be faster and more reliable than other forms of transport. It’s important though to point out that there still needs to be more work done especially in London’s outer boroughs and we urgently need to work on closing the gender gap in cycling.” Tom Fyans, Chief Executive Officer at London Cycling Campaign, said: ”London really has embraced cycling. Thanks to sustained investment by TfL, cycling now makes up a third of all tube journeys – it’s a mainstream, mass mode of transport that is healthy, safe, and both climate and congestion busting. TfL’s latest report underlines the urgency of the next steps needed – delivering high-quality safe cycle routes throughout outer as well as inner London, into every borough. That’s what will help London become the clean, green, healthy city the Mayor has committed to.” As noted in some of the above quotes, there’s plenty of room for improvement on those current daily cycle journey statistics and the infrastructure that makes it all possible. Share and hire bikes will have played their part in the rise, and there are some difficulties there too – like those created by some dockless hire bike users – that appear on the cusp of being resolved.

1. Brompton Bicycle: The Icon of Urban Cycling Brompton isn’t just a brand; it’s a revolution on wheels. Born in a London flat in 1975, Brompton began with a clear mission: to transform urban commuting. And boy, did they deliver. Every Brompton bike folds down fast into a brilliantly compact package, making it the go-to choice for city dwellers navigating crowded train platforms and tiny apartments. Innovation at its Core What sets Brompton apart is their relentless pursuit of perfection. Their bikes aren't just made; they're engineered to ensure that every ride is smoother, every fold is quicker, and every bike lasts longer. The introduction of electric models has only broadened their appeal, proving that innovation is still at the heart of their design. A Community of Riders But Brompton's impact goes beyond the bikes themselves. The brand has cultivated a vibrant community of riders worldwide. From the bustling streets of Tokyo to the hills of San Francisco, you’ll find Brompton owners racing, touring, and commuting. Annual events like the Brompton World Championship not only showcase the bike’s prowess but also bring enthusiasts together in a celebration of folding bike culture. Sustainability and the City In a world where urban mobility is increasingly about eco-friendly choices, Brompton stands out by offering a sustainable, healthy way to navigate the city. Their commitment to local manufacturing not only supports the UK economy but also keeps their carbon footprint lower than many competitors. 2. Pashley Cycles: Embracing Tradition with Modern Flair As England's oldest bicycle manufacturer, Pashley Cycles holds a special place in the hearts of British cyclists. Founded in 1926, Pashley prides itself on producing hand-built bikes that blend timeless design with modern functionality. Classic Designs, Contemporary Needs Pashley's range includes everything from classic city bikes and cargo bikes to stylish cruisers, each crafted with attention to detail and a nod to heritage. But it’s not just about looks; these bikes are built to meet today’s cycling demands, combining comfort with utility. Supporting British Craftsmanship Each Pashley bicycle is a testament to British craftsmanship, made using traditional techniques and locally sourced materials wherever possible. This commitment to quality ensures that every Pashley bike isn’t just a means of transport; it’s a piece of art. 3. Condor Cycles: Crafting Performance and Precision Founded in 1948, Condor Cycles stands out for its commitment to producing tailor-made road and track bicycles right in the heart of London. Known for their bespoke service, every Condor bike is fitted and built based on individual rider needs, ensuring top performance whether on city streets or racing circuits. Customization at Its Best Condor's unique selling point is their customization process. Customers can select from various frames, components, and finishes to create a bicycle that not only fits perfectly but also reflects their personal style and riding preferences. A Legacy of Innovation Over the decades, Condor has maintained a pioneering spirit, constantly evolving their designs to incorporate new technologies while preserving the handcrafted quality that defines them. Their bikes have been ridden by champions in world-class competitions, proving that Condor’s dedication to quality translates into real-world success. 4. Whyte Bikes: Pioneering British Innovation Whyte Bikes, launched in the late 1990s, began with a clear focus: to improve the riding experience in British conditions. They pioneered geometry that enhances stability and handling on wet and wild UK trails, setting new standards in mountain bike design. Leading in Off-Road Technology Whyte is renowned for their innovative approach to mountain bike geometry, particularly their longer wheelbase and wider bar design that provide improved control and comfort. This design philosophy has helped them stand out as leaders in off-road biking technology. Committed to Trail Enthusiasts Whyte doesn’t just sell bikes; they foster a community of trail enthusiasts, regularly engaging in trail conservation efforts and promoting sustainable practices within the biking community. Their commitment extends beyond sales to ensure that riders have safe, enjoyable, and environmentally friendly places to ride. 5. Ribble Cycles: From Local Shop to Global Icon Ribble Cycles began its journey in 1897 in Preston, England, growing from a small local shop to a globally recognized brand. They are celebrated for delivering high-quality, cost-effective bicycles, catering to both professional athletes and recreational riders. Custom Built for Everyone Ribble stands out for their direct-to-customer model, which allows them to offer high customization at competitive prices. Using their online BikeBuilder and Advanced Bike Builder platforms, customers can specify everything from frame material to gearing and aesthetics. A Culture of Cycling Ribble actively promotes a cycling culture with a strong focus on accessibility and community engagement. They host events and rides, offer extensive customer support, and maintain an active presence in cycling communities online and offline. 25 British Bicycle Manufacturers Bickerton Portables (Kent): Specialists in portable and folding bikes for the urban commuter. Bird Cycleworks (Hampshire): Designers of rugged mountain bikes tailored for trail enthusiasts. Brompton (London): Iconic creators of the world-renowned folding bikes designed for city living. Boardman (London): Providers of high-performance road bikes for competitive and recreational cycling. Cotic (Peak District): Crafters of versatile gravel and mountain bikes built for adventure. Condor (London) Founded in 1948, stands out for its commitment to producing tailor-made road and track bicycles Dolan (Liverpool): Renowned manufacturer of track bikes with a pedigree in racing. Enigma Bikes (Sussex): Makers of bespoke gravel and road bikes, blending style with performance. Factor Bikes (Norfolk): Innovators of cutting-edge road bikes known for their engineering excellence. Field Cycles (Sheffield): Artisans of custom-built road bikes with a commitment to quality. Forme Bikes (Peak District): Developers of road bikes that balance performance with rider comfort. Genesis Bikes (Milton Keynes): Producers of gravel and road bikes, known for their reliability and innovative designs. Isen (London): Modern builders of stylish gravel and road bikes for the discerning cyclist. Mason (Brighton): Constructors of high-quality gravel and road bikes that emphasize durability and design. Moulton Bikes (Bradford-on-Avon): Pioneers of the unique folding bike, designed for optimal urban transport. Mycle (London): Innovators in the electric bike market, offering modern solutions for city commutes. Pashley Cycles (Stratford-upon-Avon): Historic manufacturers of classic city bikes with timeless appeal. Orange Bikes (Halifax): Manufacturers of premier mountain bikes, designed for extreme terrains. Orro Bikes (Ditchling): Creators of premium road bikes, focusing on performance and rider experience. Ribble Cycles (Bamber Bridge): Leaders in direct-to-customer road bikes, known for customization and value. Rourke (Stoke-on-Trent): Fabricators of custom-built road bikes with a focus on personalization and craftsmanship. Shand Cycles (Edinburgh): Builders of bespoke gravel bikes, designed for both performance and comfort. Starling Bikes (Bristol): Makers of handcrafted mountain bikes, praised for their innovative designs. Woodrup Cycles (Leeds): Traditionalists in road bike manufacturing, offering bespoke builds for discerning riders. Whyte (Hastings): Specialists in mountain bikes, designed to tackle the demanding British landscape. Velomont (Norfolk): New entrants crafting mountain bikes, focusing on durability and innovative features. British bicycle brands embody more than just manufacturing; they represent a lifestyle and a heritage that continues to inspire cyclists around the globe.

What a week last week! This entire issue is dedicated to the amazing women of African cycling. These women are quickly exhibiting their prowess on the bicycle and their fierceness as competitors. This year's Tour du Burundi hosted women from Benin, Uganda, Sierra Leone (the first professional international event), Senegal, Kenya, Burkina Faso, and Burundi. The dedication and hard work of our athletes, coaches, and staff, along with a strong focus on women's cycling on the continent, paid off in a big way at the Tour du Burundi. Everything we do at Africa Rising Cycling is aimed at preparing the current generation and training the next generation—local coaches, mechanics, and soigneurs —to excel in the sport we all love. The women of Team Benin started better than their performance in 2023; however, they were not up to where the coach, Salami Avoceiten, felt they could be. If you remember, Salami spent 6 weeks in the US in intensive coaching training, on and off the bike. He dedicated himself to the firehose of knowledge our coaches pointed his way and showed his maturity and understanding of the sport in Burundi. The full results are HERE. However, the first three stages only tell part of the story. The Benin women were doing better. However, they were not firing on all cylinders as a team. Salami took the time to reach out to Coach Adrien and Coach Jock, and Coach Jock spoke to the women with Salami and laid out a strategy for Stages 4 and 5. The women delivered -- BIG TIME! On Stage 4, Hermionne, Benin's veteran female, took 2nd place in the final sprint and moved into 3rd in the General Classification (GC) thanks to the incredible teamwork of the women on her team. Stage 5, she WON the stage and retained her 3rd place GC. This win was the first time a Benin cyclist (man or woman) won a stage in an international race. The team followed up their 2023 performance with a 3rd place Team Classification win. The final event was the Grand Prix of Burundi, which, as predicted, finished with a 14-woman sprint. Hermionne took 2nd, and 17-year-old Georgette, who recently participated in and completed the Junior Women's Road Race at the World Champs in Switzerland in September, finished 3rd! Another highlight was the first-time participation by the women of Sierra Leone. Africa Rising Cycling supported the Sierra Leonean women with a preparatory training camp and flights to the event. Despite the initial challenges of their first international race, the Sierra Leonean women fought daily to finish within the time limit. In the end, a young woman, Elizabeth, became the first Sierra Leonean woman to finish the Tour du Burundi. All these women showed incredible resilience and determination, quickly learning where they needed to be to race competitively with their peers. As our motto is 'always be training,' Sierra Leone coach Roxanne was there with the former National Champion of Sierra Leone, Isata, who had her debut as the National Coach of the Sierra Leone Women's Team. Isata was not only an asset to her team but also helped the Ugandan women. Finally, a big shout out to the winners from Burkina Faso and their coach, Veronique. African women's cycling is on a meteoric trajectory, with talented riders and equally talented women coaches paving the way!.

We are now winding the clock back to the mid to late 1960s. At the time Condor Cycles were sponsoring and supplying bikes to what was to become the Condor Mackeson Team. The shop number 90 Grays Inn Rd was always busy not with customers but with riders relating as to how they had, or not, won at the weekend. One rider in particular, being Italian, would only ride a Colnago and his name was Leo Cura . He had a cafe off Pall Mall and would participate in local road races. He wasn't interested in where he finished, he just enjoyed the spectacle. In the off season we would meet up at his house in Acton and do a 2.5 hour ride. Another Italian, always very tanned, would join us. This was George Beretta who lived in Neasden and before he drove a black cab for a Living he had a small specialist importer of cycle components importer called Beretta & Penny He always wore a World Championship racing cap with the bands with 'Il campionissimo' written on it. On one of our rides he said he owned a convertible American car, a 1960 Buick Invicta that he would like to sell and I would be interested as I had just passed my driving test. I could have it for £600. He gave me a couple of photographs and from this I could see the vehicle was huge! The car was white at the time and due to its inactivity mildew was more evident than paint. I have only recently disposed of those photos as I knew that George had died and that the car must have been sold many years prior to his death. However, walking amongst the stands at the 2024 Classic Car Motor Show at the NEC with Grant, where 380 clubs were exhibiting and stretching across 6 halls I came across a 1960 Buick Invicta. I immediately said that I am sure this is George's old car even though it is in Peppermint Green and no longer white. A quick look at the number plate and I was now even more positive. Subsequently a chat with the owner confirmed that it was the very same car which he had purchased from the family in 2017. The owner is Colin Shepherd and he spent 5 years restoring it before returning it to the road in 2022. In fact all the owner's hard work has paid off as it won 'Classic American Car Magazine Car of the Year 2024. It was such a coincidence to become reacquainted with the same car I had been offered all those years ago.

Cycling UK has shared findings from a new survey, which saw 70% of respondents indicating that they wanted to see more cycle-friendly routes across the country. The survey of over 4,000 people “found that there is wide public support for cycling and better infrastructure in the UK. However, despite this support, data revealed that while the majority of the UK (92%) can ride a bike, surprisingly less than half do.” Women and cycling Looking at the survey data surrounding cycling and gender, it showed that women were almost twice as likely as men to not know how to ride a bike (11% compared to 6%), with lack of confidence also being twice that of male respondents (41% compared to 19%). A separate report published at the start of the year, titled ‘What Stops Women Cycling in London?’[1] revealed that 77% of women who cycle experienced harassment and intimidation at least once a month. Cycling UK strongly believes we need to do more to encourage women to cycle by making it safer. The charity has proposed building a greater number of well-lit, protected cycle lanes to make active travel safe, accessible and easy. It has also highlighted groups and individuals that encourage a more inclusive cycling culture in the UK, through its 100 Women in Cycling annual list. 2023 Community champions like Eilidh Murray have made incredible progress campaigning tirelessly for women’s cycle safety in her position as a trustee for the London Cycling Campaign and as the coordinator of its new Women’s Network. Road safety while cycling The survey, commissioned by Cycling UK, went on to outline how men and women equally identified road safety as the main reason they don’t cycle, (50% and 47%, respectively). The data paints a picture that despite public support for cycling, the population ultimately remain hesitant because of concerns around road safety (48%). This is further mirrored by 70% of respondents wishing to see more cycle-friendly routes, that separate them from roads where they are more likely to be injured or killed. Cycling UK highlights that countless surveys and reports have been produced over the past years, which unanimously emphasise the seismic positive impact cycling can have. In February 2024, the IPPR found that if we properly invested in active travel, we’d save the NHS £17 billion over 20 years. But going back to 2018, a survey by Cycleplan identified three-quarters of respondents noticed an improvement in their mental health after cycling. The mental and physical benefits of cycling Digging deeper into the reasons why so many of the UK support more cycle routes and better infrastructure, the public collectively recognise the benefits it has to mental and physical health. When asked, ‘Which do you think are the three most important benefits of cycling’, respondents to Cycling UK’s survey most often selected: Improves physical health (60%) Boosts fitness (50%) Enhances mental health (38%) The majority of those aged 45 and over were the most likely to recognise the benefits cycling has to physical health and fitness, with an average of 62% compared to 46% of under-45s. People in this demographic were, however, less likely to see the important impact cycling has on mental health, with an average of 36% of over-45s citing mental health as an important benefit, while the average was 41% for under-45s. Both age groups equally wanted to see more people cycling, and age did not affect respondents’ support for more cycle-friendly routes and the promotion of cycling. Sarah Mitchell, Cycling UK’s chief executive, said: “In the latter stages of the previous government, we saw the conversation around cycling become increasingly divided. “Too many politicians and commentators were attempting to co-opt cycling as part of the culture wars, by driving a wedge between people who drive and people who cycle. “With the new Culture Secretary announcing an end to the era of culture wars, we are hopeful that this kind of divisive rhetoric will be put to bed once and for all. We encourage and support debate, but we need to actively encourage this to be evidence-led and with civility at its heart. “There is a clear desire from the UK to build better cycle infrastructure and get more wheels on the road. People overwhelmingly want to get around their communities without waiting in traffic for who knows how long or having to pay to put petrol in the tank, when it would be cheaper and quicker to go by bike or foot. “Cycle lanes are cheap to build, reduce emissions, improve public health and lead to less congestion. The public recognises the benefits of cycling and is desperate to enjoy them. With political backing and funding, we can make that future a reality.” Transport infrastructure and active travel investment Earlier this year, independent research from the Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR) called for at least 10% of total transport investment to go towards active travel. This wasn’t because people living across the UK widely support cycling, which they do, but because it benefits the economy, public health and the environment in a big way. Recognising what people want from the new government, Cycling UK is repeating calls for Labour to commit to spending 10% of the total transport budget on active travel to enable people to live happier, healthier and greener lives through cycling. Cycling UK wants to see cycling and walking prioritised by this government so we can create better joined-up transport for all communities across the UK. The charity maintains that local authorities need the security of this long-term funding to have the confidence to develop and deliver ambitious plans for active travel networks. The new Transport Secretary Louise Haigh has promised to deliver the biggest overhaul to transport in a generation, having recognised how investment in transport can help achieve Labour’s commitment to “growth, net zero, opportunity, and the safety of women and girls”. Cycling in particular has the potential to positively impact not just the transport sector but also Labour’s key missions to build an NHS fit for the future, boost economic growth, and so much more. Image credit: Cycling UK

The Grand Départ Classic is your chance to follow in the tyre tracks of the Tour de France pros . This three-day event (one-day riding) offers a unique opportunity to cycle on the same roads the pros will tackle in Lille, just one week later. Currently, every year, 12,000 men still die from prostate cancer. But by funding research into safer and more accurate diagnostic tests, you can help pave the way to a screening programme, where every man at risk will get an invite to regular tests that can spot cancer early enough for a cure. Register your interest to hear more Experience a once-in-a-lifetime cycling adventure Imagine setting off from the European Metropolis Lille, pedalling past breathtaking landscapes, through the idyllic rural towns of Lens and Bethune, and out into historic Flanders. You’ll feel the wind rush past you on the final wide, perfectly flat kilometre towards the city centre. Feel like a champion as you cross that finish line, knowing you’re helping save lives. The Grand Départ Classic offers a truly unforgettable experience. When: Friday 27 - Sunday 29 June 2025 Where: Lille, France 🚲 Route: Experience the thrill of cycling Stage 1 of the Tour de France 2025. Take on the 185km Lille loop, known for its scenic route and flat terrain. Find out more information about the route on Tour de France’s official webpage , where you can check out the 2025 route map and route profile. Sign Up Today More than a team When you sign up for the Grand Départ Classic, you become part of the Prostate Cancer UK cycling community, forging friendships that could last a lifetime. Here’s what you’ll get from us: A welcome pack stuffed with fundraising tips and information Expert training advice from professional coaches, including personalised plans. Dedicated help from our team every step of the way - contact us by email or phone whenever you have a question. The ride of a lifetime awaits The Grand Départ Classic is more than just a bike ride; it's a challenge, an adventure, and a chance to fund research into transforming diagnosis and developing the treatments men need – ensuring more men are diagnosed early enough to be cured. Register your interest today

The club’s speaker for September was Jez Cox, a former competitor in cycling and duathlon, who is now a commentator and presenter. He is freelance and has worked for all the leading sports channels including GCN, Eurosport and ASO. Jez’s cycling career started at the age of thirteen with the Twickenham CC where he came under the wing of Graham Macnamee and the Pedal Club’s former president Doug Collins. Starting in cyclo cross he moved on to road racing and by 1998 he was racing in France with the C.O. Chamalieres, an elite team, where he achieved good results. By 2003 he had returned to Britain to compete in duathlons (bike and run), a discipline which suited him very well since he had many victories over the next decade, including being ranked as the top British duathlete in 2007. But no one can be a professional athlete until reaching pension age and by good fortune Jez found a new metier at the Rebourne (Hertfordshire) fete where, in the absence of any other speaker, he was handed the microphone and discovered that he was a natural as a presenter; his commentating career developed from this moment. Alongside his journalism, in 2015 he set up a cycling academy in St Albans (Oaklands Wolves Cycling Academy). When he suggested this project to British Cycling he was told it was doomed to failure and this made him determined to prove them wrong. Perhaps BC didn’t know that he already had his foot in the door at Oaklands College, having done some consultancy work for them, but it is impressive that the academy is now flourishing nine years after its foundation. Unlike many other speakers (with the exception of John Dutton!) Jez was relatively optimistic about the current state of British Cycling. He feels that the departure of Team Sky has benefited the organisation, that the strong growth of women’s racing is an important advance and he believes it will be possible to bring at least some of the middle aged ‘mamils’ into cycling proper. Another hope is that facilities already existing in schools could be better used by the cycling world. Perhaps the most encouraging point for the Pedal Club is that this career started from an ‘old fashioned’ local club (the Twickenham CC, founded 1893 has produced many stars in the past). The great majority of Pedal Club members started in this way, and I’m sure we were all pleased to hear that this path can still lead to success in the twenty-first century. The Lunch was again held at the Civil Service Club in Whitehall and was attended by 34 members and guests. Chris Lovibond, September 2024. .